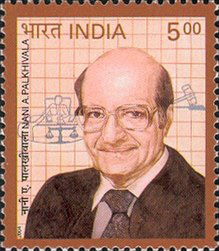

Shri. N. A. Palkhivala is widely acknowledged to have been known as a great many things to a great many people. For the unsuspecting law student, his name creeps up as a reverential echo out of the many pages of the textbook on constitutional law. He has been known to be publicly called out as ‘Gods gift to India’, a ‘Court Room Genius’, a role model and more often, in casual conversations by the seniors of the Bombay bar, just ‘Nani’. It is when the law student is done grappling with the game changing concepts that were a direct contribution of this colossus at the bar in the guise of the celebrated ‘Keswananda Bharati’ Judgement, that the appreciation for the contribution towards the development of the law made by this doyen of the bar actually starts eclipsing the sheer awe that his very name commands from the highest court of the land to the lowest. A teacher, an author, a counsel an economist and a guru, he continues to be the role model that every lawyer asks his Juniors to adopt.

The thoughts, freedoms, concepts that are taken for granted by every citizen today, achieve a special significance when the realization dawns, that these were never perhaps explicitly conferred, but were carved out, by Judges committed, not to the government of the day but to the rule of law, aided and abetted by lawyers and lifetime students of constitutional law and constitutionalism. The protections that are enjoyed and taken for granted today are the direct result of the strong building blocks pooled together by the galaxy of jurists both on and off the bench, forming a ‘laxman rekha’ of concepts that till date guard the sacred freedoms that the founding fathers of our country fought so hard to obtain and preserve for us, the people of India. Amongst this galaxy of galaxy of stars, the star that shines brightest is that of Padma Vibhushan Mr. N. A. Palkhivala.

In our effort to compile some of his Important cases argued before the various ‘Constitutional’ Benches of the Supreme Court, we encountered the problem of plenty. The sheer number of cases argued by Mr. Palkhivala before the Supreme Court with bench with a strength of five Judges or less was enough to be a separate publication by itself! We have however, taken an effort to distill out some of the landmark cases he has appeared in with a Bench strength of six Judges or more, in the hope that they shall still prove invaluable to the readers. The discussion made is not exhaustive or absolute, but is more to merely ‘highlight’ a few of the landmark cases that he was involved with.

Gujarat University & Onr. v. Shri Krishna Ranganath Mudholkar AIR 1963 SC 703

Background:

A Candidate, Shrikant joined the St. Xavier’s College affiliated to the University of Gujarat, in the First Year Arts class and was admitted in the section in which instructions were imparted through the medium of English. After successfully completing the First Year Arts course in March 1961, Shrikant applied for admission to the classes preparing for the Intermediate Arts examination of the University through the medium of English. The Principal of the College informed Shrikant that in view of the provisions of the Gujarat University Act, 1949 and the Statutes 207, 208 and 209 framed by the Senate of the University, as amended in 1961 he could not without the sanction of the University permit him to attend classes in which instructions were imparted through the medium of English. Shri Krishna, father of Shrikant then moved the Vice Chancellor of the University for sanction to permit Shrikant to attend the “English medium classes” in the St. Xavier’s College. The Registrar of the University declined to grant the request, but by another letter Shrikant was “allowed to keep English as a medium of examination” but not for instruction.

Various Grounds were taken up in the Writ Petition by the Petitioners out of which the Six Judge Bench of the Supreme Court decided to determine the answer to the following two questions:

(1) whether under the Gujarat University Act, 1949 it is open to the University to prescribe Gujarati or Hindi or both as an exclusive medium of media of instruction and examination in the affiliated colleges

(2) whether legislation authorising the University to impose such media would infringe Entry 66 of List I, Seventh Schedule to the Constitution.

Held:

The Judgement was in the favour of the Respondents with a majority of five judges to one. The majority held that the power to legislate in respect of primary or secondary education is exclusively vested in the States by Item 11 of List II, and power to legislate on medium of instruction in institutions of primary or secondary education must therefore rest with the State Legislatures. Power to legislate in respect of medium of instruction is, however, not a distinct legislative head; it resides with the State Legislatures in which the power to legislate on education is vested, unless it is taken away by necessary intendment to the contrary. Under Items 63 to 65 the power to legislate in respect of medium of instruction having regard to the width of those items, must be deemed to vest in the Union. Power to legislate in respect of medium of instruction, insofar it has a direct bearing and impact upon the legislative head of coordination and determination of standards in institutions of higher education or research and scientific and technical institutions, must also be deemed by Item 66 List I to be vested in the Union.

The State has the power to prescribe the syllabi and courses of study in the institutions named in Entry 66 (but not falling within Entries 63 to 65) and as an incident thereof it has the power to indicate the medium in which instruction should be imparted. But the Union Parliament has an overriding legislative power to ensure that the syllabi and courses of study prescribed and the medium selected do not impair standards of education or render the coordination of such standards either on an all-India or other basis impossible or even difficult. Thus, though the powers of the Union and of the State are in the Exclusive Lists, a degree of overlapping is inevitable. It is not possible to lay down any general test which would afford a solution for every question which might arise on this head. On the one hand, it is certainly within the province of the State Legislature to prescribe syllabi and courses of study and, of course, to indicate the medium or media of instruction. On the other hand, it is also within the power of the Union to legislate in respect of media of instruction so as to ensure coordination and determination of standards, that is, to ensure maintenance or improvement of standards. The fact that the Union has not legislated, or refrained from legislating to the full extent of its powers does not invest the State with the power to legislate in respect of a matter assigned by the Constitution to the Union. It does not, however, follow that even within the permitted relative fields there might not be legislative provisions in enactments made each in pursuance of separate exclusive and distinct powers which may conflict. Then would arise the question of repugnancy and paramountcy which may have to be resolved on the application of the “doctrine of pith and substance” of the impugned enactment.

UOI v. Harbhajan Singh Dhillion 1971(2) SCC 779

Background:

The Judgement was passed by a majority of four judges to three dissenting out of a seven Judge bench, while examining the definition of ‘net wealth’ in the Wealth Tax Act, 1957 (27 of 1957), as amended by Section 24 of the Finance Act, 1969, by including agricultural land in assets for the purpose of calculating tax on the capital value of net wealth. The question raised was whether the amendment of the definition of ‘assets’ by withdrawing exemption in respect of agricultural land was within the competence of the Parliament.

Held:

Under the distribution of powers under in the constitution, the field of agriculture and agricultural land was almost exclusively entrusted to the states. Such a restriction must be held to be a result of a calculated policy as in our country, agricultural land would be by far the largest asset and capable of bringing a substantial amount of tax. Those who excluded such an asset from Entry 86 and gave power over it to the states could not have possibly thought of including such an excluded item of taxation in the residuary power of the union under Article 248(i). The lists do not confer powers; they merely demarcate the legislative fields.

Ujjam Bai v. State of Uttar Pradesh (1963) 1 SCR 778

Background:

The larger bench (seven judges) of the Supreme Court was seized with the issue as to whether the validity of an order made with jurisdiction under an Act which is Intra vires and good law in all respects, or of a notification properly issued thereunder, liable to be questioned in a petition under Art. 32 of the Constitution on the sole ground that the provisions of the Act, or the terms of the notification issued thereunder, have been misconstrued?

The Judgement was passed by a majority of six judges to one (out of which J.L. Kapur, J., did not venture into the question of law and dismissed the petition on the basis on delay).

Held:

An order of assessment made by an authority under a taxing statute which is intra vires and in the undoubted exercise of its jurisdiction cannot be challenged on the sole ground that it is passed on a misconstruction of a provision of the Act or of a notification issued thereunder. Nor can the validity of such an order be questioned in a petition under Art. 32 of the Constitution. The proper remedy for correcting an error in such an order is to proceed by way of appeal, or if the error is an error apparent on the face of the record, then by an application under Art. 226 of the Constitution. Article 32 of the Constitution does not give the Supreme Court an appellate jurisdiction such as is given by Arts. 132 to 136. Article 32 guarantees the right to a constitutional remedy and relates only to the enforcement of the rights conferred by Part III of the Constitution. Unless a question of the enforcement of a fundamental right arises, Article 32 does not apply.

The question of enforcement of a fundamental right will arise if a tax is assessed under a law which is

(a) void under Art. 13 or

(b) is ultra vires the Constitution or

(c) where it is subordinate legislation, it is ultra vires the law under which it is made or inconsistent with any other law in force.

If the tax is assessed and/or levied by an authority

(a) other than the one empowered to do so under the taxing law or

(b) in violation of the procedure prescribed by the law or

(c) in colourable exercise of the powers conferred by the law, No fundamental right is breached and consequently no question of enforcing a fundamental right arises where a tax is assessed and levied bona fide by a competent authority under a valid law by following the procedure laid, down by that law, even though it be based upon an erroneous construction of the law except when by reason of the construction placed upon the law a tax is assessed and levied which is beyond the competence of the legislature or is violative of the provisions of Part III or of any other provisions of the Constitution.

A mere misconstruction of a provision of law does not render the decision of a quasi-judicial tribunal void (as being beyond its jurisdiction). It is a good and valid decision in law until and unless it is corrected in the appropriate manner. So long as that decision stands, despite its being erroneous, it must be regarded as one authorised by law and where, under-such a decision a person is held liable to pay a tax that person cannot treat the decision as a nullity and contend that what is demanded of him is something which is not authorised by law. The position would be the same even though upon a proper construction, the law under which the decision was given did not authorise such a levy.

CIT v. Bai Shirinbai K. Kooka (1962) 46 ITR 86 (SC)

Background:

A three Judge Bench of the Supreme Court had referred the question as to the seven Judge Bench of the Supreme Court. The Court was concerned with as to how the computation of profit made by the Assessee by a sale of her shares as a trading activity be computed. The Assessee had purchased the shares in a previous year below market price but had in the assessment year under consideration , converted the shares into stock in trade and carried out a business activity. The question was as to whether the historical actual cost price of the share should have been taken for the purpose of calculation of profit or whether the market price of the shares as on date of conversion of the shares into stock in trade.

The Judgement was in the favour of the Respondent Assesseee by a majority judgement of six judges to one dissenting.

Held:

The basis for computing the actual profits in the present case must be the ordinary commercial principles on which actual profits are computed. Normally the commercial profits out of the transaction of sale of an article must be the difference between what the article cost the business and what it fetched on sale. So far as the business or trading activity was concerned, the market value of the shares as on April 1, 1945 was what the shares cost the business. The High Court did not create any legal fiction of a sale when it took the market value as on April 1, 1945 as the proper figure for determining the actual profits made by the assessee. That the assessee later sold the shares in pursuance of a trading activity was not in dispute; that sale was an actual sale and not a notional sale; that actual sale resulted in some profits. The only fair measure of assessing trading profits in such circumstances was to take the market value at one end and the actual sale proceeds at the other, the difference between the two being the profit or loss as the case may be. In a trading or commercial sense this seemed to the Supreme Court to accord more with reality than with fiction.

Keshav Mills Co. Ltd. v. CIT (1965) 56 ITR 365 (SC)

Background:

The Bench of seven judges of the Supreme Court was seized of the issue as to whether they should, and in what circumstances, if at all should they reconsider their early decisions. The Attorney General had urged that the decision of a five Judge Bench in the case of Petlad Turkey Red Dye Works Co. Ltd., Petlad v. CIT [(1963) Supp 1 SCR 871 : AIR 1959 SC 1177] and the descition in the case of New Jehangir Vakil Mills Ltd. v. CIT [(1960) 1 SCR 249] needed to be reconsidered due to the importance of the matter.

Held:

The seven Judge bench of the Supreme Court passed an unanimous order.

In a proper case, the Supreme Court has inherent jurisdiction to reconsider and revise its earlier decisions. In exercising the inherent power, however, the Court would naturally like to impose certain reasonable limitations and would be reluctant to entertain pleas for the reconsideration and revision of its earlier decisions, unless it is satisfied that there are compelling and substantial reasons to do so. It is general judicial experience that in matters of law involving questions of construing statutory or constitutional provisions, two views are often reasonably possible and when judicial approach has to make a choice between the two reasonably possible views, the process of decision making is often very difficult and delicate. When the Court hears appeals against decisions of the High Courts and is required to consider the propriety or correctness of the view taken by the High Courts on any point of law, it would be open to this Court to hold that though the view taken by the High Court is reasonably possible, the alternative view which is also reasonably possible is better and should be preferred. In such a case, the choice is between the view taken by the High Court whose judgment is under appeal, and the alternative view which appears to this Court to be more reasonable; and in accepting its own view in preference to that of the High Court, the Court would be discharging its duty as a court of appeal. But different considerations must inevitably arise where a previous decision of this Court has taken a particular view as to the construction of a statutory provision. When it is urged that the view already taken by this Court should be reviewed and revised, it may not necessarily be an adequate reason for such review and revision to hold that though the earlier view is a reasonably possible view, the alternative view which is pressed on the subsequent occasion is more reasonable. In reviewing and revising its earlier decision, the Court should ask itself whether in the interests of the public good or for any other valid and compulsive reasons, it is necessary that the earlier decision should be revised. When the Court decides questions of law, its decisions are, under Article 141, binding on all courts within the territory of India, and so, it must be the constant endeavour and concern of the Court to introduce and maintain an element of certainty and continuity in the interpretation of law in the country. Frequent exercise by the Court of its power to review its earlier decisions on the ground that the view pressed before it later appears to the Court to be more reasonable, may incidentally tend to make law uncertain and introduce confusion which must be consistently avoided. That is not to say that if on a subsequent occasion, the Court is satisfied that its earlier decision was clearly erroneous, it should hesitate to correct the error; but before a previous decision is pronounced to be plainly erroneous, the Court must be satisfied with a fair amount of unanimity amongst its members that a revision of the said view is fully justified. It is not possible or desirable, and in any case it would be inexpedient to lay down any principles which should govern the approach of the Court in dealing with the question of reviewing and revising its earlier decisions. It would always depend upon several relevant considerations: —What is the nature of the infirmity or error on which a plea for a review and revision of the earlier view is based? On the earlier occasion, did some patent aspects of the question remain unnoticed, or was the attention of the Court not drawn to any relevant and material statutory provision, or was any previous decision of this Court bearing on the point not noticed? Is the Court hearing such plea fairly unanimous that there is such an error in the earlier view? What would be the impact of the error on the general administration of law or on public good? Has the earlier decision been followed on subsequent occasions either by this Court or by the High Courts? And, would the reversal of the earlier decision lead to public inconvenience, hardship or mischief? These and other relevant considerations must be carefully borne in mind whenever this Court is called upon to exercise its jurisdiction to review and revise its earlier decisions. These considerations become still more significant when the earlier decision happens to be a unanimous decision of a Bench of five learned Judges of this Court.

MCD v. Birla Cotton, Spinning and Weaving mills, Delhi & Ors. AIR 1968 SC 1232

Background:

The Supreme Court was seized with the issue of the constitutionality of delegation of taxing powers to municipal corporations and the effect of the Validation Act, passed by Parliament, in connection with tax on the consumption or sale of electricity levied by the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (hereinafter referred to as “the Corporation”) from July 1, 1959 to March 31, 1966. It was contended before a seven Judge bench of the Supreme Court that the Validation Act has failed in its object inasmuch as it did not provide for the levy of tax and merely validated the rates fixed by the resolution of June 24, 1959. It was also contended that Section 150 is unconstitutional inasmuch as it suffers from the vice of excessive delegation of legislative power and is therefore ultra vires and no tax could be levied by the Corporation thereunder. Sub-section (1) of Section 150 left it to the Corporation, at a meeting, to pass a resolution for the levy of any of the optional taxes by prescribing the maximum rate. The Corporation was also given the power to fix the class or classes of persons or the description or descriptions of articles and properties to be taxed, for this purpose. It also had the power to lay down the system of assessment and exemptions, if any, to be granted. The contention of the Respondent was that Section 150(1) delegated completely unguided power to the Corporation in the matter of optional taxes and suffers from the vice of excessive delegation and is unconstitutional.

Held:

The Supreme Court held in favour of the Appellant Municipal Corporation by a majority of five judges to two. Four Judgements were passed, out of which one will dissenting.

The Court held that principle is well established that essential legislative function consists of the determination of the legislative policy and its formulation as a binding rule of conduct and cannot be delegated by the legislature. Nor is there any unlimited right of delegation inherent in the legislative power itself. This is not warranted by the provisions of the Constitution. The legislature must retain in its own hands the essential legislative functions and what can be delegated is the task of subordinate legislation necessary for implementing the purposes and objects of the Act. Where the legislative policy is enunciated with sufficient clearness or a standard is laid down, the courts should not interfere. What guidance should be given and to what extent and whether guidance has been given in a particular case at all depends on a consideration of the provisions of the particular Act with which the Court has to deal including its preamble. The nature of the body to which delegation is made is also a factor to be taken into consideration in determining whether there is sufficient guidance in the matter of delegation. It will depend upon the circumstances of each statute under consideration; in some cases guidance in broad general terms may be enough; in other cases more detailed guidance may be necessary.

Powers, Privilages and Immunities of State Legislatures, Re v. (1965) 1 SCR 413

Background:

The President had formulated five questions for the opinion of this Court under Article 143(1) of the Constitution of India. The occasion for the reference was a sharp conflict that arose between the Vidhan Sabha (Legislative Assembly) of the Uttar Pradesh State Legislature, and the High Court of that State. That conflict arose because the High Court had ordered the release on bail of a person whom the Assembly had committed to prison for contempt. The Assembly considered that the action of the Judges making the order and of the lawyer concerned in moving the High Court amounted to contempt and started proceedings against them on that basis, and the High Court, thereupon, issued orders restraining the Assembly and its officers from taking steps in implementation of the view that the action of the Judges and the lawyer and also the person on whose behalf the High Court had been moved amounted to contempt.

The following questions were raised before the seven Judge Bench constituted to answer the questions:

“(1) Whether, on the facts and circumstances of the case, it was competent for the Lucknow Bench of the High Court of Uttar Pradesh, consisting of the Hon’ble Mr. Justice N. U. Beg and the Hon’ble Mr. Justice G. D. Sahgal to entertain and deal with the petition of Mr. Keshav Singh challenging the legality of the sentence of imprisonment imposed upon him by the Legislative Assembly of Uttar Pradesh for its contempt and for infringement of its privileges and to pass orders releasing Mr. Keshav Singh on bail pending the disposal of his said petition;

(2) Whether, on the facts and circumstances of the case, Mr. Keshav Singh by causing the petition to be presented on his behalf to the High Court of Uttar Pradesh as aforesaid, Mr B. Solomon, Advocate, by presenting the said petition and the said two Hon’ble Judges by entertaining and dealing with the said petition and ordering the release of Shri Keshav Singh on bail pending disposal of the said petition committed contempt of the Legislative Assembly of Uttar Pradesh;

(3) Whether, on the facts and circumstances of the case, it was competent for the Legislative Assembly of Uttar Pradesh to direct the production of the said two Hon’ble Judges and Mr. B. Solomon, Advocate, before it in custody or to call for their explanation for its contempt;

(4) Whether, on the facts and circumstances of the case, it was competent for the Full Bench of the High Court of Uttar Pradesh to entertain and deal with the petitions of the said two Hon’ble Judges and Mr. B. Solomon, Advocate, and to pass interim orders restraining the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Uttar Pradesh and other respondents to the said petitions from implementing the aforesaid direction of the said Legislative Assembly; and

(5) Whether a Judge of a High Court who entertains or deals with a petition challenging any order or decision of a legislature imposing any penalty on the petitioner or issuing any process against the petitioner for its contempt or for infringement of its privileges and immunities or who passes any order on such petition commits contempt of the said legislature and whether the said legislature is competent to take proceedings against such a Judge in the exercise and enforcement of its powers, privileges and immunities.”

Held:

Two separate Judgements were passed in the said reference, the second broadly concurring with the conclusions of the former except for the final question which was considered too general.

(1) On the facts and circumstances of the case, it was competent for the Lucknow Bench of the High Court of Uttar Pradesh, consisting of N. U. Beg and G. D. Sahgal, JJ., to entertain and deal with the petition of Keshav Singh challenging the legality of the sentence of imprisonment imposed upon him by the Legislative Assembly of Uttar Pradesh for its contempt and for infringement of its privileges and to pass orders releasing Keshav Singh on bail pending the disposal of his said petition.

(2) On the facts and circumstances of the case, Keshav Singh by causing the petition to be presented on his behalf to the High Court of Uttar Pradesh as aforesaid, Mr B. Solomon, Advocate, by presenting the said petition, and the said two Hon’ble Judges by entertaining and dealing with the said petition and ordering the release of Keshav Singh on bail pending disposal of the said petition, did not commit contempt of the Legislative Assembly of Uttar Pradesh.

(3) On the facts and circumstances of the case, it was not competent for the Legislative Assembly of Uttar Pradesh to direct the production of the said two Hon’ble Judges and Mr B. Solomon, Advocate, before it in custody or to call for their explanation for its contempt.

(4) On the facts and circumstances of the case, it was competent for the Full Bench of the High Court of Uttar Pradesh to entertain and deal with the petitions of the said two Hon’ble Judges and Mr B. Solomon, Advocate, and to pass interim orders restraining the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Uttar Pradesh and other respondents to the said petitions from implementing the aforesaid direction of the said Legislative Assembly; and

(5) In rendering our answer to this question which is very broadly worded, we ought to preface our answer with the observation that the answer is confined to cases in relation to contempt alleged to have been committed by a citizen who is not a member of the House outside the four walls of the legislative chamber. A Judge of a High Court who entertains or deals with a petition challenging any order or decision of a legislature imposing any penalty on the petitioner or issuing any process against the petitioner for its contempt, or for infringement of its privileges and immunities, or who passes any order on such petition, does not commit contempt of the said legislature; and the said legislature is not competent to take proceedings against such a Judge in the exercise and enforcement of its powers, privileges and immunities. In this answer, we have deliberately omitted reference to infringement of privileges and immunities of the House which may include privileges and immunities other than those with which we are concerned in the present Reference.

The Ahmedabad St. Xaviers College Society and Onr. v. State of Gujarat (1974) 1 SCC 717

The nine Judge Bench of the Supreme Court was his larger Bench has been constituted to consider the scope of the fundamental rights under Article 30(1), the inter-relationship of those rights with the rights under Article 29(1), the scope of the regulatory powers of the State vis-a-vis the rights under Article 30(1), and in the light of the view taken on the several aspects aforesaid to consider the validity of certain impugned provisions of the amended Gujarat University Act, 1949. The attempt on behalf of the State of Gujarat had been to raise the crucial issues which go to the root of the rights conferred on the minorities to establish educational institutions of their choice and whether the State could treat the majority and minority educational institutions equally, an issue upon which the Court has pronounced on earlier occasions.

Mr. Palkhivala appeared for the intervenors in the said matter. It was submitted that regulatory rights were permissible up to the point where they do not in substance interfere with the right of administration but leave management free of control and permit the minority to mould the institution as it deems fit and they do not destroy the essence of the element of choice. It was also contended that the minorities right to administer educational institutions is not a right that can be exercised in vacuo. A university has no power to prescribe as a condition of affiliation that the minority should surrender its fundamental right to administer the institutions of its choice.

Held:

The bench of nine Judges passed six separate Judgements upon the issue which had been time and again been raked up in the past about the rights of the minority institutions. The orders generally do not starkly veer away from each other. The right given under Article 30 is the right to establish an educational institution of its choice. It was held that thought the rights under Article 30(1) is ‘couched’ in absolute terms, it would be subject to reasonable regulation. It was held that the state cannot indirectly do what it could not directly do, and therefore though there are powers that enable regulation for affiliation of Universities, these must not be of that character that involve the abridgment of the right of the linguistic minorities to administer and establish educational institutions of their choice. The fundamental right under Article 30 cannot be bartered away / surrendered or waived by any voluntary act.

Indra Sawhny & Ors. v. UOI & Ors. 1992 Supp (3) SCC 217

Background:

A bench of nine Judges of the Supreme Court was constituted to settle the legal position related to affirmative action and reservation.

Sri N. A. Palkhivala submitted that : a secular, unified and caste-less society is a basic feature of the Constitution. Caste is a prohibited ground of distinction under the Constitution. It ought be erased altogether from the Indian Society. It can never be the basis for determining backward classes referred to in Article 16(4). The report of the Mandal Commission, which is the basis of the impugned Memorandums, has treated the expression “backward classes” as synonymous with backward castes and has proceed to identify backward classes solely and exclusively on the basis of caste, ignoring all other considerations including poverty. It has indeed invented castes for Non-Hindus where none exists. The report has divided the nation into two sections, backward and forward, placing 52% of the population in the former section. Acceptance of Report would spell disaster to the unity and integrity of the nation. If half of the posts are reserved for backward classes, it would seriously jeopardise the efficiency of the administration, educational system, and all other services resulting in backwardness of the entire nation. Merit will disappear by deifying backwardness. Article 16(4) is broader than Article 15(4). The expression “backward class of citizens” in Article 16(4) is not limited to “socially and educationally backward classes” in Article 15(4). The impugned Memorandums, based on the said report must necessarily fall to the ground along with the Report. The main thrust of Sri Palkhivala’s was against the Mandal Commission Report.

Held:

The matter was heard by a nine judge bench and the court with a majority of six judges to three upheld the constitutionality, validity and enforcement of the reservations for backward castes subject to certain conditions and perquisites. The 10% additional reservation for the economically backward class was struck down as unconstitutional and struck down.

The Judges constituting the majority and the minority and those of the minority have taken an independent stand on the various issues questions and aspects that were before them.

R. C. Cooper v. UOI (1970) 1 SCC 248

Background:

In 1969, the Vice-President (acting as President) promulgated an ordinance transferring to and vesting the undertaking of 14 named commercial banks in corresponding new banks set up under the Ordinance. Under the Ordinance the entire undertaking of every named commercial bank was taken over by the corresponding new bank, and all assets and contractual rights and all obligation to which the named bank was subject stood transferred to the corresponding new bank. The Chairman and the Directors of the Banks vacated their offices. To the named banks survived only the right to receive compensation to be determined in the manner prescribed. Compensation, unless settled by agreement, was to be determined by the Tribunal, and was to be given in marketable Government securities. The entire business of each named bank was accordingly taken over, its chief executive officer ceased to hold office and assumed the office of the Custodian of the corresponding new bank, its directors vacated offices, and the services of the administrative and other staff stood transferred to the corresponding new bank. The named bank had thereafter no assets, no business, no managerial, administrative or other staff, was incompetent to use the word “Bank” in its name, because of the provisions contained in Section 7(1) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949, and was liable to be dissolved by a notification of the Central Government.

The eleven Judge bench of the Supreme Court was hearing the petitions challenging the competence of the President to promulgate the Ordinance. The case is often famously referred to as the ‘Bank nationalisation case’

Held:

There were two Judgements passed by the eleven Judge Bench, with the Majority Judgement being for ten Judges and the sole dissent was authored by Ray, J. The majority declared that the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Act 22 of 1969 was invalid and the action taken or deemed to be taken in exercise of the powers under the Act was declared unauthorised. It was held that :

(a) the Act was within the legislative competence of the Parliament; but

(b) it made hostile discrimination against the named banks in that it prohibited the named banks from carrying on banking business, whereas other Banks — Indian and Foreign — were permitted to carry on banking business, and even new Banks may be formed which may engage in banking business;

(c) it in reality restricted the named banks from carrying on business other than banking as defined in Section 5(b) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949; and

(d) that the Act violated the guarantee of compensation under Article 31(2) in that it provided for giving certain amounts determined according to principles which were not relevant in the determination of compensation of the undertaking of the named banks and by the method prescribed the amounts so declared cannot be regarded as compensation.”

Madhav Rao Jivaji Rao Scindia & Ors. v. UOI & Ors. (1971) 1 SCC 85

Background:

The Indian States formed a significant but separate part of India before they merged with the rest of India. The Privy Purses and the Privileges were continued till 6th September, 1970. Their payment or enjoyment was a part of the guarantee of the Constitution. However ,the All India Congress Committee passed a Resolution on 25th June, 1967 for their abolition. In furtherance of this resolution the Union Home Ministry held several conferences with the representatives of the Rulers. Although shorn of all but a shadow of their former power and panoply the Rulers seemed to regard themselves as something different from the people or perhaps, as princes in exile. They had their Concord, their Intendant-General and Conciliar Committee, thereby evoking a certain measure of hostility among persons who were oblivious of the constitutional transition in India Government of India repeated their intention of withdrawing the recognition of the Rulers and stoppage of the Privy Purses and Privileges, and was prepared only for a negotiated settlement as to the terms on which the abolition should take place. The Concord of Princes was not prepared to enter into any negotiations and were chary of a fresh settlement which might be broken just as simply as the past solemn engagements and assurances.

According to the petitioners, the failure to amend the Constitution resulted in the retention in it, of the articles relevant to the Rulers’ rights. These articles, particularly Articles 291 and 362 continued the obligation of the Government to pay the Privy Purses and also to recognise the Privileges. The Privy Purses stood charged on and were to be paid out of the Consolidated Fund of India and even Parliament could not vote upon them. The assurances and guarantees being that of the people in their Constitution, the Executive Government could not by the indirect device of withdrawing the recognition of the Rulers avoid the obligations created by the Constitution. These assurances and guarantees of the Constitution, the Accession and Integration were but steps and the fixation of Privy Purses and the recognition of the Privileges was no doubt a historical fact but the guarantee flowed from the Constitution and were independent of the historical fact, and had thus to be carried out according to the constitutional provisions. They based their claim not on the agreements or the covenants but on the constitutional provisions. According to them, the order of the President was in violation of the spirit and meaning of Articles 366(22), 291 and 362 and was an affront to Parliament which had turned down the move for amendment of these articles. The President’s action robbed the articles of their content which Parliament did not allow to be done and thus the order of the President indirectly had the effect of amending the Constitution. The President’s order itself was said to be mala fide, ultra vires since his power was to recognise a Ruler at a time and for the time being or to withdraw recognition from a Ruler for cogent and valid reasons, naming in his place a successor, and not to withdraw recognition from all Rulers en masse for no reason except that the concept of Rulership was considered outmoded or that some persons held the view that it should not be continued. According to the petitioners the Gaddi of a Ruler had to be filled in accordance with the law and custom of the family and could not be left vacant. The vast power to withdraw recognition from all the Rulers at the same time without nominating any successor could not and did not flow from the definition of a Ruler in Article 366(22) which contemplated the continuance of a Ruler who had signed the Merger Agreement or his successor. The President was thus guilty of a breach of his duties under the Constitution and acted outside his jurisdiction.

This case is famously referred to as the ‘privy purses case’.

Held:

The Supreme Court with a majority of nine Judges (three concurring judgements) to two (two separate dissents) struck down the Presidential order abolishing the privy purses. The Court held that:

The Courts had jurisdiction to interpret and to determine the true meaning of Articles 366(22), 291, 362 and 363 of the Constitution of India. The bar to the jurisdiction of the Courts by Article 363 was a limited bar: it did not arise merely because the Union of India set up a plea that the dispute falling within Article 363 is raised. The Court would give effect to the constitutional mandate if satisfied that the dispute arises out of any provision of a covenant which is in force and was entered into or executed before the commencement of the Constitution and to which the predecessor of the Government of India was a party, or that it is in respect of rights, liabilities or obligations accruing or arising under any provision of the Constitution relating to a covenant. But since the right to the Privy Purse arises under Article 291 the dispute in respect of which did not fall within either clause, the jurisdiction of the Court was not excluded. The jurisdiction of the Court was not excluded, in respect of disputes relating to personal rights and privileges which are granted by statutes so long as they remain in operation.

It was declared that the order made by the President on September 6, 1970, “de-recognising” the Rulers was illegal and on that account inoperative, and the petitioner would be entitled to all his pre-existing rights and privileges including the right to the Privy Purse, as if the order had not been made. The President is not invested with any political power transcending the Constitution, which he may exercise to the prejudice of citizens. The powers of the President arise from and are defined by the Constitution. Validity of the exercise of those powers is always amenable to the jurisdiction of the Courts, unless the jurisdiction is by precise enactment excluded. Power of this Court under Article 32, or of the High Courts under Article 226, cannot be bypassed under a claim that the President has exercised political power.

Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalvaru and Ors v. State of Kerala (1973) 4 SCC 225

Background:

The state government of Kerala introduced the Land Reforms Amendment Act, 1969. According to the act, the government was entitled to acquire some of the sect’s land of which Kesavananda Bharti was the chief.

On 21st March 1970, Kesavananda Bharti moved to Supreme Court under Section 32 of the Indian Constitution for enforcement of his rights which guaranteed under Article 25 (Right to practice and propagate religion), Article 26 (Right to manage religious affairs), Article 14 (Right to equality), Article 19(1)(f) (freedom to acquire property), Article 31 (Compulsory Acquisition of Property). When the petition was still under consideration by the court, the Kerala Government passed another act i.e. Kerala Land Reforms (Amendment) Act, 1971.

After the landmark case of Golaknath v. State of Punjab, the Parliament passed a series of Amendments in order to overrule the judgment of the Golaknath’s case. In 1971, the 24th Amendment was passed, in 1972, 25th and 29th Amendment were passed subsequently. Mr. N. A. Palkhivala had also appeared in the case of ‘Golaknath’ which was with a bench strength of eleven Judges. Sri. Kesavananda Bharati challenged the validity of the said amendments and the Court referred the matter to a larger bench of 13 judges with the following questions:

-

Whether the decision of this Court in Golaknath v. State of Punjab correct?

-

What is the extent of the power of the Parliament to amend the Constitution under Article 368?

-

Whether the 24th Constitutional (Amendment), Act 1971 is Constitutionally valid or not?

-

Whether the 25th Constitutional (Amendment), Act 1972 is Constitutionally valid or not?

-

Whether the 29th Constitutional (Amendment) Act, 1971 is valid or not?

Held:

The judgment that was delivered by the 13-judge bench was by a thin majority of 7:6. The learned judges delivered 11 separate judgments.

It was held by the apex court by a majority of 7:6 that Parliament can amend any provision of the Constitution to fulfil its socio-economic obligations guaranteed to the citizens under the Preamble subject to the condition that such amendment wouldn’t change the basic structure of the Indian Constitution. The majority decision was delivered by S.M. Sikri CJI, K.S. Hegde, B.K. Mukherjea, J. M. Shelat, A.N. Grover, P. Jagmohan Reddy JJ. & Khanna J. Whereas, the minority opinions were written by A.N. Ray, D.G. Palekar, K.K. Mathew, M.H. Beg, S.N. Dwivedi & Y.V. Chandrachud. The minority bench wrote different opinions but was still reluctant to give unfettered authority to the Parliament. The landmark case was decided on 24th April 1973. It was held that the Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution to the extent that such amendment does not change the basic structure of the Indian Constitution. Thus, in exercising the power of amendment, the Parliament cannot change the Basic structure or essential features of the Constitution.

The court found the answer to the question that was left unanswered in Golaknath regarding the extent of amending power with the Parliament. The answer which the court deduced was Doctrine of Basic Structure. This doctrine implies that though Parliament has the prerogative to amend the entire Constitution, including the Chapter on Fundamental Rights, but subject to the condition that they cannot in any manner interfere with the features so fundamental to this Constitution that without them it would be spiritless. Justice Hegde and Justice Mukherjea, opined that Indian Constitution is not a mere political document rather it is a social document based on a social philosophy. Every philosophy like religion contains features that are basic and circumstantial. While the former cannot be altered the latter can have changes just like the core values of a religion cannot change but the practices associated with it may change as per needs & requirements. The list of what constitutes basic structure is not exhaustive & the court through its majority descition left it to the courts to determine these fundamental elements. It is upon the courts to see that a particular amendment violates Basic structure or not. This question has to be considered in each case in the context of a concrete problem.

The Questions raised were answered as follows:

-

Golak Nath’s case was over-ruled;

-

Article 368 did not enable Parliament to alter the basic structureof frame-work of the constitution;

-

Section 2(a) and (b) of the Constitution (Twenty-fourth Amendment) Act, 1971 were valid;

-

The first part of Section 3 of the Constitution (Twenty-fifth Amendment) Act, 1971 was valid.

-

The second part, namely, “and no law containing a declaration that it is for giving effect to such policy shall be called in question in any court on the ground that it does not give effect to such Policy” was invalid;

-

The Constitution (Twenty-ninth Amendment) Act, 1971 was valid.

The Reconsideration of the Kesawanada Bharti Judgement

It is perhaps telling that the most famous case in which Shri. N. A. Palkhivala appeared was not destined to have any result. The then Chief Justice A.N. Ray, who was a part of the dissenting minority in the case of the Kesawanada Bharti Judgement famously constituted a bench of the Supreme Court in order to reconsider it. Various literature exists in the public realm of the twists and turns that occurred and the historical observation of Khanna J., in his autobiography “Neither Roses nor thorns” dedicates an entire chapter to the ill-fated exercise. It is but fitting that the same be included in the important constitutional cases that Shri Palkhivala appeared in, for what could be as important as the re-consideration of the ‘basic structure’ doctrine?

Justice Khanna writes that a few days after the judgement of Mrs. Gandhi’s election had been announced, in the middle of the emergency, he heard from a colleague that a move was a foot to overrule the decision in the case of Kesawanada Bharti. He was initially dismissive about the same, however after some days a bench of thirteen Judges was indeed constituted by the Chief Justice. There had been no order of any bench asking for reference of the matter to a larger bench. This irregularity had been pointed out in court. Justice Khanna observed that the main argument to oppose the reconsideration was advanced by Nani Pankhivala. In one of the most impassioned addresses, Nani said that no case had been made for re-consideration of the matter, more particularly at the time when the emergency was in full force. He added that there could be as such time no full discussion nor full reporting of arguments. He also challenged the press to report what he said in the court. Nani Palkhivala was still on his feet when the court rose for the day and the next day the bench was dissolved and the Chief Justice decided not to go ahead with the matter.

The Court, on the dissolution of the Bench, did not ‘hold’ anything. The only record we have on the result of the case is recorded by Justice Khanna in his autobiography (‘neither roses nor thorns’ published by EBC) and in his personal capacity “My feeling and that of some of my colleagues was that the height of eloquence to which Palkhivala rose on that day had seldom been equalled and never surpassed in the history of the Supreme Court.”