-

Introduction

Rapid strides in the field of technology has made it possible for businesses to participate in the economic life of a jurisdiction without local physical presence. Advancement of technology and digitalization of economy has resulted in tax challenges such that the present international taxation framework lagged in creation of a mechanism for appropriate taxation of digital transactions. The current tax treaty rules allocate taxing rights to a (market) jurisdiction based on physical presence i.e. existence of a permanent establishment (‘PE’) is the threshold to tax businesses which participate in a jurisdiction.

International community has identified tax challenges posed by digitalized economy and took note of the business structures used by many multinational enterprises such that their overall tax bill was negligible or low. At OECD level, this was identified as one of the focus area of Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (‘BEPS’) Action Plan, which resulted in 2015 BEPS Action Plan 1 Report1. Further work on this subject was undertaken by the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS (‘Inclusive Framework’) which has an agenda of delivering a consensus-based solution to tackle tax challenges arising from digitalization of the economy. The Inclusive Framework has developed a two-pillar project – aimed at introducing equity and fairness in the tax systems. Pillar One is focused on nexus and profit allocation aspects and Pillar Two is focused on a global minimum tax. The work of Inclusive Framework is ongoing, and it is expected that a consensus-based solution will be delivered soon.

With specific focus on developing countries, tax consequences of digitalized economy were also recognized by the UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters (‘UN Tax Committee’), which started engaging itself in this work in the 15th session. It was decided to focus on developing tax treaty provision which will enable jurisdictions to apply their domestic law and tax digital business models. The objective of UN Tax Committee was to deliver a solution which is relatively simple to comply, and which will result in a definite tax share for the market jurisdictions. It was identified that taxing rights with respect to income from automated digital services (‘ADS’) should be distributed amongst treaty partners by adding Article 12B to the UN Model Double Taxation Convention (‘UN MC’).

This article discusses the finalized version of Article 12B and related Commentary proposed to be inserted in the UN MC. It also discusses how few members / countries have expressed their concerns on inclusion of Article 12B in their bilateral tax treaties; how jurisdictions have started adopting uncoordinated unilateral measures and the inter-play of Article 12B with the OECD/ G20’s two-pillar project (an approach largely backed by developed nations).

-

The Background

During the 20th session of UN Tax Committee, a Drafting Group was formed of 13 (later 14) members to develop an additional provision in the UN MC to allocate additional taxing rights with a view to supplement resources of developing countries. The Drafting Group presented a proposal for inclusion of a new Article 12B (“Income from Automated Digital Services”) in the UN MC, which was circulated to all the members of the UN Tax Committee for comments.

Further, an amended draft of Article 12B was discussed in the 21st session and the members voted to include an Article 12B in the 2021 version of the UN MC. Later, finalized version of Article 12B and its Commentary was presented during the 22nd Session held in April 2021 and it was decided to include the finalized version in the 2021 update of UN MC2.

The objective of new Article 12B is to draw a new nexus rule allowing contracting states to tax income from certain digital services, with a view to achieve reallocation of profits to market jurisdictions through a bilateral approach. With this background, this article proceeds to discuss the contents of Article 12B, mechanism prescribed to allocate taxing rights and views of certain dissenting members on the new nexus rule.

-

Understanding Article 12B: Taxing Automated Digital Services

3.1 Introductory remarks

Article 12B consists of 11 paragraphs and its construct is broadly similar to other passive income articles like dividend, interest, royalty, etc. The first paragraph provides for taxing right to the contracting state where the income recipient is a resident, however, it does not provide that such income will be exclusively taxed in the state of residence.

Further, the second paragraph gives taxing right to the contracting state in which the income from ADS arises in accordance with the domestic law of such state. However, if the beneficial owner of such income is a resident of other contracting state, this paragraph limits the taxing right to a fixed gross rate, to be mutually agreed by the two treaty partners. In this regard, the UN Tax Committee, in the finalized version of the Commentary recommends a ‘modest’ tax rate of 3 or 4 percent3.

In addition to the above and unlike other passive income Articles of UN MC, Article 12B provides an option to the beneficial owner of income from ADS to elect for net basis taxation on its ‘qualified profits’ in the source state. The mechanics of net basis taxation rule is discussed in detail hereinafter at section 3.3 below.

3.2 Scope of ‘Automated Digital Services’

3.2.1 Definition of ADS

The term ‘ADS’ is defined in para 5 of Article 12B to mean “any service provided on the internet or another electronic network, in either case requiring minimal human involvement from the service provider”. Further, para 6 of Article 12B lists examples of digital services which may constitute ADS.

The Commentary explains the scope of above definition in the below manner:

-

A service is regarded as automated if users can avail such service automatically through equipment and systems being in place;

-

The test of minimum human involvement is to be applied from perspective of the service provider; it is possible that a user may have to input certain parameters to use an automated system to obtain the desired result;

-

As an indicator of the concept of automated services, the Commentary discusses the ability of service provider to scale-up and offer the services to new customers / users with no or minimal human involvement; and

-

The aspect of providing a service over the internet or other electronic network is different from other service provision methods such as on-site physical performance of a service.

Therefore, the general definition of ADS has two keys thresholds – (i) mode of service provision/ manner in which service is provided to the user and (ii) level of human intervention by the service provider. The Commentary also discusses that the test of human involvement should be applied at the stage of provision of service and hence, human involvement in the course of developing, maintaining and updating the system will be irrelevant here.

3.2.2 Activities which may constitute ADS

Paragraph 6 of Article 12B starts with the words “The term automated digital services includes especially….” and then it goes on to list the services. Use of these words may give an impression that the said para deals with an inclusion list i.e. services which will qualify as ADS. However, the Commentary states that services listed in para 6 are those which will often constitute as ADS. An important passage of the Commentary (para 57) reads as under:

“Paragraph 6 therefore simply provides an indication that an activity may constitute an automated digital service; it does not provide that an activity listed therein necessarily is an automated digital service.”

Therefore, every service listed in para 6 of Article 12B will be subject to the test of general definition of ADS. The services listed in para 6 and a brief description of such services is tabulated below:

| Service nomenclature | Brief description of the service |

| Online advertising services | Online services which are aimed at placing advertisements on a ‘digital interface’. This includes services for purchase, storage and distribution of advertising messages, and for monitoring of advertising and measurement of its performance. |

| Supply of user data | This is understood to mean supply of data (such as a user’s habits, spending, personal interests, etc.) to a third-party customer in respect of users of a digital interface, which is collected, compiled, aggregated or otherwise processed into data through an automated algorithm. |

| Online search engines | This means making a digital interface available to users for the purpose of allowing them to search across the Internet, where users are charged for access (for instance, a subscription model). |

| Online intermediation platform services | This involves providing a digital interface to users to enable interactions between them, for sale, hire, advertisement of goods, services, etc. |

| Social media platforms | A platform available on a digital interface to facilitate interaction between users for a range of activities such as social and professional networking websites, video or image sharing platforms, etc. |

| Digital content services | This implies automated provision of content in digital form such as computer programs, applications, music, videos, books etc. The service is beyond simply making a digital interface available to the users, there should be ability to access digital content. |

| Online gaming | This implies making a digital interface available to users to interact with each other in the same game environment i.e. multiplayer gaming environment. |

| Cloud computing services | This service includes provision of standardized on-demand network access to information technology resources including infrastructure as a service, platform as a service or software as a service. For instance, storage service, webhosting, computing service, etc. |

| Standardized online teaching services | This implies provision of online education program to unlimited number of users, which does not require (a) live presence of an instructor; or (b) significant customization for users. An example of such a service is pre-recorded series of lectures. |

3.2.3 Activities outside the scope of ADS

Article 12B has a specific paragraph to deal with the inter-play of this Article with Articles dealing with ‘royalty’ and ‘fees for technical services’. Paragraph 7 of Article 12B provides that provisions of Article 12B will not apply if the payments underlying the income from ADS services qualify as ‘royalty’ or ‘fees for technical services’ under Article 12 / 12A of the UN MC. Interestingly, from Indian treaty network perspective, generally, royalty and fees for technical services is subject to tax in the source state at the gross tax rates of 10 or 15 percent. This means that in case of a conflict, inter-play is likely to retain a higher taxing rate with the source state (assuming the contracting states negotiate a modest tax rate for Article 12B).

Further, the Commentary provides a list of services which should not qualify as ADS; this is intended to avoid uncertainty in interpretation of scope of ADS. The exclusion list includes services which require customization (i.e. human involvement) to cater to specific user requirements or those where goods / service delivery does not happen over an electronic network.

The exclusion list is described in the below table:

|

Service nomenclature |

Brief description of the service |

|

Customized professional services |

These services, though delivered online, require customization to each client, through use of professional judgement and bespoke interactions. For instance, services such as legal, accounting, financial, architecture etc. |

|

Customized online teaching services |

Here the service is customized to the needs of a student or limited group of students. Internet or electronic network is only used as a means to establish communication between the teacher and the student. |

|

Services providing access to Internet / an electronic network |

This means providing access to the internet or to an electronic network irrespective of the mode of delivery, namely over wire, lines, cables, etc. |

|

Online sale of goods and services other than ADS |

This category applies to sellers who use a digital platform to sell their own non-digital goods and non-digital services to the customers. |

|

Revenue from the sale of a physical good, irrespective of network connectivity (‘internet of things’) |

This means sale of physical goods even if affected through digital network should not qualify as ADS if there is no separate identifiable payment for ADS. |

3.3 Alternate profit allocation rule: Net basis taxation

As discussed in section 3.1 above, the beneficial owner of income from ADS is offered a choice to opt for net basis taxation for the whole of a tax year under consideration. Paragraphs 3 and 4 of Article 12B provides for such option, wherein the beneficial owner may request the contracting state, in which the income arises, to be taxed on net basis at the tax rate provided in the domestic law of such state. The Commentary explains the rationale of this alternate profit allocation rule by referring to a situation wherein application of gross basis taxation may result in higher tax liability for the beneficial owner compared to application of net basis taxation. For instance, gross basis taxation would not be beneficial for taxpayers who have a global business loss or a loss in the relevant business segment during the taxable year.

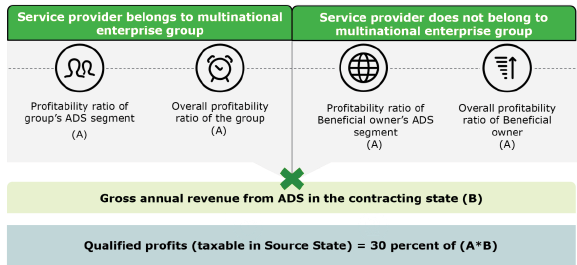

The mechanism prescribed to exercise net basis taxation is as under:

-

Beneficial owner (referred as ‘taxpayer’ in this section) is required to compute ‘profitability ratio’ of ADS business segment and in case segmental accounts are not maintained, the overall ‘profitability ratio’ will be considered;

-

‘Profitability ratio’ is understood to mean annual profits divided by annual revenue as per the financial statements of the taxpayer. Further, unless bilaterally agreed, annual profits would be profit before tax, with certain adjustments such as exclusion of dividend income, gains/ losses in connection with shares, add back of expenses not deductible for corporate income-tax purposes, etc.4;

-

Taxpayer will have to apply the profitability ratio to the gross annual revenue derived from the source state. This will result in determination of overall profits vis-s-vis ADS revenue from the source state and 30 percent of such overall profits (known as ‘qualified profits’) is considered as taxable in the source state5;

-

The ‘qualified profits’ will then be taxed at the rate of tax provided in the domestic tax law of the source state.

In case the taxpayer belongs to a multinational enterprise group6, the profitability ratio will have to be computed at the group level, provided it is higher than the taxpayer level profitability ratio. The rationale of this, as explained in the Commentary, is to neutralize the possible reduction of entity level profitability due to tax driven related party transactions.

A peculiar feature of net basis approach, with reference to a taxpayer who belongs to a multinational enterprise group, is that if the source state does not possess the segmental or overall profitability ratio of the multinational enterprise group, net basis taxation will not be permitted in such cases and accordingly, gross basis taxation will have to be followed by the taxpayer. In this regard, the Commentary discusses that the information can be supplied under the exchange of information mechanism or the taxpayer may share such information to the tax authorities of source state.

The above discussion on computation of net basis taxation is summarized in the below table:

Therefore, though referred to as net basis taxation, strictly speaking, the above-mentioned profit allocation rule differs from the arm’s length principle to allocate taxing rights. This is having regard to the following:

-

This approach views ‘revenue’ at par with ‘assets’ and ‘employees’ in terms of its contribution in generation of profits; based on which profits attributable to the source state is deemed to be 30 percent;

-

Computation of overall profits from ADS revenue derived from the source state is based on group level profitability ratio – it is assumed that inter-group arrangements will be driven by tax considerations; and

-

Mechanism to compute annual profits (before tax) is not finalized and some brief guidance on this is discussed in the Commentary. An aspect here will be possibility of the ultimate parent of the multinational enterprise group (located in a third country) adopting accounting standard rules which may not be compatible with computation mechanism agreed by treaty partners.

3.4 Revenue sourcing rule

The revenue sourcing rule is incorporated in paras 9 & 10 of Article 12B. Paragraph 9 specifies that income from ADS arises in the contracting state in which the payer is a resident or in which the payer has a PE or fixed base (and such payment is borne by the PE or fixed base). Further, paragraph 10 deems income from ADS not to arise in the contracting state in which the payer is a resident if the payment towards ADS is borne by the PE or fixed base in a third state.

An important feature of the sourcing rule narrated above is that it does not give regard to the location of users of the service. In other words, it is not necessary that the consumption of services should take place in the contracting state in which the payer is a resident or has a PE or fixed base.

To illustrate the above, let us take an example7 of an enterprise of State A which provides search engine services to users that are located in State B, without requiring any payment in consideration for such services, it collects data regarding those users’ profile. Such information allows that enterprise to provide online advertising services to a person resident in State C that is interested in reaching potential consumers of its own services and products in State B. Therefore, the enterprise of State A receives payment from person resident in State C to target advertisements to specific potential consumers in State B. In this case, application of Article 12B will allocate taxing right to State C (i.e. jurisdiction where the advertiser is a resident), however, State B does not get any taxing right.

In the above example, the target audience for the advertiser is in State B. In other words, use of search engine facilitates targeted marketing for the advertiser in State B and enables it to engage with its (prospective) customers. Such non-physical interaction improves the value of advertiser’s products / services and increases the sales in market jurisdiction. In such cases, taxing the advertisement revenue in the jurisdiction where the advertiser is located, and ignoring the market jurisdiction completely, may fail to achieve the objective of fair and equitable distribution of taxing rights.

Another example could be in the case of an arrangement consisting of online marketplace which lists accommodation facilities for accommodation seekers.

In the above case, Mr A who lives in State S books an accommodation in State D through a facilitator Company B located in State R. Here, application of Article 12B would result in the facilitation fee being subject to tax in State S, being the state of residence of the payer. However, State D, where the accommodation is booked will not get any right to tax the facilitation fee earned by the service provider.

-

Implementation: Key challenges

Certain members of the UN Tax Committee have expressed concerns on practical implementation of the above-discussed bilateral approach. The Commentary discusses some of the issues flagged by such members, which are as under:

-

Reallocation of profits of multinational enterprise group to market jurisdictions is best achieved through a multilateral approach (work on which is ongoing at the OECD/G20 level);

-

The sourcing rule does not adequately address the value generated by data collected in relation to users of free digital services (example discussed in the previous section);

-

Another concern relates to application of Article 12B to small payments and payments by individuals acquiring services for personal use; this is likely to increase the administrative burden since withholding tax mechanism may not be feasible in such situations;

-

Foreign service providers may pass on additional tax costs on to the consumers through ‘gross-up’ clauses in the contracts.

A specific mention is made in the Commentary that countries sharing the above concerns may not wish to include Article 12B in their bilateral tax treaties. While the Commentary does not list down the names of countries which hold such view, it will be interesting to see how many nations will proceed to adopt Article 12B in their tax treaties, especially the developed nations. Also, should the Inclusive Framework, which includes participation by developing countries, arrive at a consensus-based multilateral solution, the countries will have to elect one of the approach. The choice will depend on various factors such as administrative convenience, level of allocation of taxing rights, ability to provide certainty to taxpayers, etc.

-

Taxing digital transactions: The Indian Approach

In 2016, India had introduced digital tax in the form of ‘equalization levy’ on online advertisement services at the rate of 6 percent. Thereafter, in April 2020, the scope of ‘Equalisation Levy’ was expanded to include a 2 percent levy on e-commerce transactions, involving online sale of goods or provision of services by non-resident e-commerce operators.

Further, the concept of significant economic presence (‘SEP’) was introduced in the domestic law in 2018 with the intent to bring non-resident technology giants deriving significant revenue from large user base in India within the tax net. However, the said concept remained inapplicable on account of the thresholds not being specified. Recently, the Indian Government has notified8 the relevant thresholds for non-residents to constitute SEP in India – these rules are applicable from financial year 2021-22 onwards.

India has been announcing that its measures to tax digital transactions is temporary until a global consensus is reached. It will be interesting to see if India approaches its treaty partners to insert Article 12B in its tax treaties – considering it is a sizeable market jurisdiction for digital transactions. This will also depend on how OCED/G20 proceeds to arrive at a global consensus on the two-pillared approach.

Like India, many other countries have introduced digital services tax (DST) regimes in their local tax laws. The scope of taxes introduced on digital transactions by such jurisdictions is varied; in form of direct and / or indirect taxes. With reference to many such DST regimes (for instance, India, Australia, Italy, Spain, etc.), the US has perceived the same to be a discriminatory move targeting the US Digital Hub. In January 2021, the office of the U.S. Trade Representative (‘USTR’) issued reports and findings that such DSTs discriminates against US companies, is inconsistent with prevailing principles of international taxation, and burdens or restricts US companies.

-

Conclusion

Article 12B proposed to be introduced in the 2021 update of UN MC is a one of the stepping stone in addressing the tax challenges posed by digitalization of the economy. It is fairly easy to understand and has moved fast compared to the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework. Further, officials from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund have welcomed and expressed support to the UN approach. With more and more countries looking at adoption of digital service tax regime in their domestic law (may be an interim measure), Article 12B just gives an option to implement a bilateral solution.

Also, it is a known fact that UN’s approach on tax policy matters is usually in the interest of developing countries; however, with the consensus-based solution being developed at the OECD/G20 level, one will have to wait and see if the developed economies show interest in adopting the bilateral approach and incorporate Article 12B in the tax treaties. Also, there are some implementation related concerns which will require attention of the jurisdictions desirous of adopting Article 12B in their tax treaties.

-

Addressing the tax challenges of the Digital Economy, Action 1 – 2015 Final Report, OECD/G20 BEPS Project.

-

For ease of reference, the finalized version of Article 12B and the related Commentary proposed to be introduced in UN MC, hereinafter, will be referred as ‘Article 12B’ and ‘the Commentary’ respectively.

-

Para 29 of the Commentary lists various factors which contracting states should consider while deciding the level of taxation at source. For instance, it discusses that a high rate of tax might result in non-resident pass over the tax cost to the consumers in the source state.

-

Discussed in paragraph 47 of the Commentary on Article 12B. It may be noted that the above-mentioned adjustments discussed in the Commentary are not a definite list of exclusions and appear to be in nature of examples. This may become a subject matter of discussion for contracting states and hence, treaty partners may negotiate a specific formulaic approach for calculation of annual profits – with a view to ensure certainty in application of this rule.

-

Allocation of 30 percent of profits to source jurisdiction is prescribed keeping in view the contribution of markets in generation of profits and by assigning equal weightage to the role of assets, employees and the revenue in generation of profits. In view of UN Tax Committee, this rate is a fair and reasonable share to both jurisdictions and is adopted with a view to achieve certainty [Reference: Para 50 of the Commentary].

-

Paragraph 4 of Article 12B reads as under:

“4. For the purposes of paragraph 3, multinational enterprise group” means any “group” that includes two or more enterprises, the tax residence for which is in different jurisdictions. Further, for the purposes of paragraph 3, the term “group” means a collection of enterprises related through ownership or control such that it is either required to prepare Consolidated Financial Statements for financial reporting purposes under applicable accounting principles or would be so required if equity interests in any of the enterprises were traded on a public stock exchange.”

-

This example is discussed in paragraph 75 of the Commentary to Article 12B.

-

Notification No. 41 /2021/ F. No. 370142/11/2018-TPL dated 3 May 2021.