GST, being value added tax system, imposes tax at every stage of value addition and at every stage there may immerge distinct or new commodity which may be subject to tax at different rates of GST. One of the primary reasons behind introduction of GST was to eliminate the cascading or “tax on tax” effect prevalent in earlier indirect tax regime. As we have variety of rate of taxes under GST, mainly 0%, 5%, 12%, 18% and 28%, implemented in India law makers envisaged a situation where inwards supplies are taxed at higher rate in comparison with rate of tax on output supplies. Classic example of the above situation is rate of tax on synthetic or artificial filament yarns being taxed @12% whereas fabric made out these yarns is being taxed @ 5%. In the country like India where variety of tax rates are implemented, it is very difficult to achieve the real benefit of implementation of GST by removing cascading effect. In fact, in many cases supplies which are exempt from GST becomes more costly to consumers rather than supplies taxable at lower rate of tax.

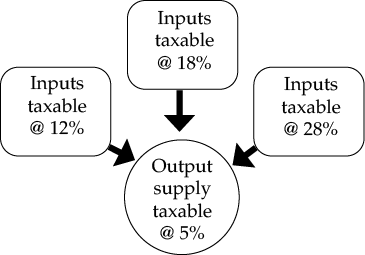

Inverted Duty Structure is a situation where the supplier pays higher rate of tax on its input supplies, and pays comparatively lower rate of tax on its output supply. Consequently, a large amount of credit of tax paid on input supplies is accumulated. This would result in cascading effect of taxes if loaded to product cost with consequent increase in the cost to consumer which is against the basic principle of GST being a consumption tax.

Section 54 (3) of the CGST act, 2017 envisage a situation where the credit has accumulated on account of rate of tax on inputs being higher than the rate of tax on output supplies (other than nil rated or fully exempt supplies), except supplies of goods or services or both as may be notified by the Government on the recommendations of the Council. For ease of understanding section 54 (3) of the CGST act, 2017 is reproduced below:

54 (3) Subject to the provisions of sub-section (10), a registered person may claim refund of any unutilised input tax credit at the end of any tax period:

Provided that no refund of unutilised input tax credit shall be allowed in cases other than––

(i) zero rated supplies made without payment of tax;

(ii) where the credit has accumulated on account of rate of tax on inputs being higher than the rate of tax on output supplies (other than nil rated or fully exempt supplies), except supplies of goods or services or both as may be notified by the Government on the recommendations of the Council:

Provided further that no refund of unutilised input tax credit shall be allowed in cases where the goods exported out of India are subjected to export duty:

Provided also that no refund of input tax credit shall be allowed, if the supplier of goods or services or both avails of drawback in respect of central tax or claims refund of the integrated tax paid on such supplies.

Although plain reading of sub-section (3) of section 54 allows refund of unutilised input tax credit and seems to have very wider applicability, but there are three proviso’s to this sub-section and specially first proviso narrow down the section applicability only to the extent of two scenarios as mentioned in that proviso. Case (ii) mentioned in first proviso relates to refund in a case which is popularly known as inverted duty structure.

There are three types of inward supplies defined under the GST law being ‘input’, ‘input services’ and ‘capital goods’, but the law makers have chosen only ‘inputs’ for comparison of rate of tax with output supplies. In place of ‘inputs’ if ‘inward supplies’ word could have been used then the situation would have been different all together.

Rule 89(5) deals with the refund in such situations and in the case of refund on account of inverted duty structure, refund of input tax credit shall be granted as per the following formula:

Maximum Refund Amount = {(Turnover of inverted rated supply of goods and services) x Net ITC ÷ Adjusted Total Turnover} – tax payable on such inverted rated supply of goods and services.

Explanation:- For the purposes of this sub-rule, the expressions –

Net ITC shall mean input tax credit availed on inputs during the relevant period other than the input tax credit availed for which refund is claimed under sub-rules (4A) or (4B) or both; and

“Adjusted Total turnover” and “relevant period” shall have the same meaning as assigned to them in sub-rule (4)

Explanation to Rule 89(5) of the CGST Rules, 2017 restricts the benefit of such refund only to the extent of the ‘goods’ procured by the supplier and that too excluding capital goods. This means that the refund of input tax paid on ‘services’ cannot be availed.

Hon’ble Gujarat High Court had the occasion for judicial scrutiny of the above provisions in the case of VKC Footsteps India Pvt. Ltd. vs. UOI -2020 (7) TMI 726 and held that the above Explanation is ultra vires to the provisions of the Act as the CGST Act categorically provides that refund of ‘unutilized Input tax credit’ and Rules cannot go to disallow a benefit which is granted by the parent legislation.

Contrary to the above decision of the Hon’ble Gujarat High Court, the Hon’ble Madras High Court passed an order in favour of revenue in the case of TVL. Transtonnelstroy Afcons Joint Venture v. UOI- 2020 (9) TMI 931. Hon’ble Madras High Courtarrived at the following conclusion:

-

Section 54(3)(ii) does not infringe Article 14.

-

Refund is a statutory right and the extension of the benefit of refund only to the unutilised credit that accumulates on account of the rate of tax on input goods being higher than the rate of tax on output supplies by excluding unutilised input tax credit that accumulated on account of input services is a valid classification and a valid exercise of legislative power.

-

Therefore, there is no necessity to adopt the interpretive device of reading down so as to save the constitutionality of Section 54(3)(ii).

-

Section 54(3)(ii) curtails a refund claim to the unutilised credit that accumulates only on account of the rate of tax on input goods being higher than the rate of tax on output supplies. In other words, it qualifies and curtails not only the class of registered persons who are entitled to refund but also the imposes a source-based restriction on refund entitlement and, consequently, the quantum thereof.

-

As a corollary, Rule 89(5) of the CGST Rules, as amended, is in conformity with Section 54(3)(ii).

Consequently, it is not necessary to interpret Rule 89(5) and, in particular, the definition of Net ITC therein so as to include the words input services.

Recently Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Union Of India & Ors. Versus VKC Footsteps India Pvt Ltd- 2021 (9) TMI 626 – SC, upheld the judgement of Madras High Court in the case of TVL. Transtonnelstroy Afcons Joint Venture vs. UOI (supra) and held that having considered this batch of appeals, and for the reasons which have been adduced in this judgment, we affirm the view of the Madras High Court and disapprove of the view of the Gujarat High Court.

So far as issue related to calculation of Net ITC for the purpose of quantification of refund amount as per rule 89(5) is concerned, that controversy seems to has been settled by the Hon’ble SC and the Net ITC shall include ITC related to ‘Inputs’ being goods other than capital goods and excluding ‘input services’ only.

Another controversy has arisen due to Circular No.135/05/2020 – GST dated 31st March 2020 where the CBIC has clarified that the benefit of refund under inverted duty structure is not available where the input and the output supplies are the same. Relevant para 3.2 of the above circular is reproduced below:

3.2 It may be noted that refund of accumulated ITC in terms clause (ii) of sub-section (3) of section 54 of the CGST Act is available where the credit has accumulated on account of rate of tax on inputs being higher than the rate of tax on output supplies. It is noteworthy that, the input and output being the same in such cases, though attracting different tax rates at different points in time, do not get covered under the provisions of clause (ii) of sub-section (3) of section 54 of the CGST Act. It is hereby clarified that refund of accumulated ITC under clause (ii) of sub-section (3) of section 54 of the CGST Act would not be applicable in cases where the input and the output supplies are the same.

There are many instances of reduction of rate of tax under GST or where concessional rate of tax has been prescribed for supplies to certain specified recipient for example Concessional GST rate on scientific and technical equipments supplied to public funded research institutions has been prescribed by Notification No. 45/2017 – Dated: 14-11-2017 – CGST (Rate). These types of rates variation accumulate credit with the traders and there is no alternate mechanism provided for the same.

Recently the same issue came for consideration before the Hon’ble Gauhati High Court in the case of BMG Informatics Pvt. Ltd., vs The Union Of India – 2021 (9) TMI 472 dated 2nd September 2021. The Hon’ble Gauhati High Court held as below:

-

Consequently, in view of the clear unambiguous provisions of Section 54(3) (ii) providing that a refund of the unutilized input tax credit would be available in the event the rate of tax on the input supplies is higher than the rate of tax on output supplies, we are of the view that the provisions of paragraph 3.2 of the circular No.135/05/2020-GST dated 31.03.2020 providing that even though different tax rate may be attracted at different point of time, but the refund of the accumulated unutilized tax credit will not be available under Section 54(3)(ii) of the CGST Act of 2017 in cases where the input and output supplies are same, would have to be ignored.

-

However, we have taken note of that the circular No.135/05/2020-GST dated 31.03.2020 was issued in exercise of the powers under Section 168(1) of the CGST Act of 2017. As already noted, Section 168(1) of the CGST Act of 2017 pertains to a situation where the Central Board of Indirect Tax and Customs considers it necessary and expedient to do so for the purpose of uniformity in implementing the CGST Act of 2017. In other words, the provisions of Section 168(1) can be invoked to bring in uniformity in the implementation of the CGST Act of 2017. In the instant case, when the provisions of Section 54(3)(ii) of the CGST Act of 2017 are unambiguous and explicitly clear in nature, there is no requirement of bringing in any uniformity in the implementation of the Act and the provisions of Section 54(3)(ii) would have to be applied in the manner it is provided in the Act itself.

The concept of refund under inverted duty structure is contentious, complicated and difficult to implement. This was also accepted by the Hon’ble Finance Minister in her budget speech 2021 and the relevant para 176 of the budget speech 2021 is reproduced below:

-

The GST Council has painstakingly thrashed out thorny issues. As Chairperson of the Council, I want to assure the House that we shall take every possible measure to smoothen the GST further, and remove anomalies such as the inverted duty structure.

Recently in the 45th GST Council meeting held on 17th September 2021 following decision has been taken as per the press release dated 17.09.2021, which is worth considering to understand the complexity of the issue related to the inverted duty structure:

“Council decides to set up 2 GoMs to examine issue of correction of inverted duty structure for major sectors and for using technology to further improve compliance, including monitoring.”

From the above discussion it’s clear that controversies relating to inverted duty structure are not going to end soon and any efforts done to mitigate the issues related to inverted duty structure may further increase the confusion and complexities, unless single GST rate is worked out for most of the goods and services barring very minimal exceptions and now after having experience of revenue collections for more than 4 years that seems to be not very difficult.

(Source : Article published in Souvenir released at National Tax Conference held at Katra on 2nd & 3rd October, 2021)